Made a RISC-V Emulator Running Xv6

I’ve made a RISC-V emulator that can run xv6, a simple Unix-like OS for education. All the source code of the emulator is available in the d0iasm/rvemu repository. In this article, I’m going to introduce emulator’s features implemented for running the OS, by looking back at the source code that made major changes.

Note: The source code at each point in time is not necessarily the correct implementation, as I sometimes fixed implementation errors after the commit.

October 22, 2019 (143c7d5: src/lib.rs)

This is the first commit after creating a repository. I used the template in the tutorial of Rust and WebAssembly because I wanted to use Rust for my curiosity and compile it to WebAssembly to run the emulator in the browser. Wasm-bindgen imported in src/lib.rs is the library to communicate with Rust and JavaScript.

There’s nothing yet to function as an emulator.

October 30, 2019 (2274ebf: src/cpu/instruction.rs)

I implemented add instruction to add two registers, and addi instruction to add registers and a 12-bit immediate value.

RISC-V is an open standard instruction set architecture, and you can download PDFs of the specification from riscv.org/specifications. First, I’m going to implement a CPU instruction one by one by reading Volume I: Unprivileged ISA in the specifications.

The role of a CPU is to execute a program consisting of binaries sequentially by three steps: fetching, decoding, and execution.

- Fetch: Fetches the next instruction to be executed from the memory where the program is stored.

- Decode: Splits an instruction sequence into a form that makes sense to the CPU. How to interpret the instruction is defined in Volume I: Unprivileged ISA at riscv.org/specifications.

- Execute: Performs the action required by the instruction. In hardware, arithmetic operations such as addition and subtraction are performed by ALU (Arithmetic logic unit), but in the emulator I decided to implement it without worrying about small components.

November 11, 2019 (2d59abc: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented RV32I instructions, which defines basic integer operations for 32-bit architecture.

The basic integer operations should be implemented in all platforms. In addition, other instructions can be extended to suit the application. The basic integer operations for 32-bit architectures are called RV32I, and the basic integer operations for 64-bit architectures are called RV64I.

In Volume I: Unprivileged ISA, a combination of a base ISA (RV32I or RV64I) plus the following extensions is called RV32G or RV64G (general-purpose ISA).

- RV32I/RV64I: The most basic instructions, including integer, bit, shift, load and store in memory, and branch instructions

- RV32M/RV64M: Instructions for multiplication and division.

- RV32A/RV64A: Atomic Instructions.

- RV32F/RV64F: Instructions for single precision floating points.

- RV32D/RV64D: Instructions for double precision floating points.

- Zicsr: Instructions for manipulating control and status registers.

- Zifencei: The fence instruction (to guarantee the order in which memory is written)

RV32I defines 40 instructions, but I implemented 37 instructions except for fence, ecall, and ebreak. fence is an instruction to keep the memory consistency between multiple hardware threads. If you have multiple hardware threads, you have multiple program counters storing the location of the instruction to be executed next. The more hardware threads exist, the more programs that can be executed at the same time, which leads to higher speed.

Since the emulator only implements one hardware thread, I decided that fence is unnecessary for now. Also, ecall and ebreak will be required when implementing the privilege modes defined in Volume II: Privileged Architecture, but not yet implemented at this time.

November 18, 2019 (caea7c6: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented RV64I by adding 12 instructions to RV32I and the registers are extended to 64 bits.

The basic operations in RV64I is the same as RV32I, but the effective number of bits is different. For example, add instruction in RV32I is to add two 32-bit registers, but add instruction in RV64I is to add two 64-bit registers. Addw is used in RV64I to add two 32-bit registers.

November 19, 2019 (44c0584: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented RV64M, which defines instructions for multiplication and division.

In multiplication, if the result is a large number that does not fit within 64 bits (this is called arithmetic overflow), only the lower 64 bits are stored in the register and the upper bits are ignored. Also, in division, all bits are set as a result of division by 0. In this way, RISC-V does not raise any exceptions due to arithmetic operations. This is because in order to handle exceptions, it is necessary to implement the mechanism for exceptions defined in Volume II: Privileged Architecture, which can be a detriment of smaller hardware.

December 30, 2019 (67558bd: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented RV64F, which defines single-precision floating-point operations. The floating-point numbers comply with IEEE 754-2008 standardized by IEEE.

RISC-V CPU has 32 integer registers, but when you implement floating-point operations, you need to have an additional 32 floating-point registers. It also has a control and status register fcsr which holds the status of a rounding mode and flags to indicate whether or not an exception is raised by the operation. For example, if a number is divided by 0, the third bit of fcsr (DZ flag) is set.

There are five rounding modes, but I haven’t implemented them yet. (The following is from wikipedia IEEE 754)

- round to nearest, where ties round to the nearest even digit in the required position (the default and by far the most common mode)

- round to nearest, where ties round away from zero (optional for binary floating-point and commonly used in decimal)

- round up (toward +∞; negative results thus round toward zero)

- round down (toward −∞; negative results thus round away from zero)

- round toward zero (truncation; it is similar to the common behavior of float-to-integer conversions, which convert −3.9 to −3 and 3.9 to 3)

January 2, 2020 (83ef66c: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented RV64D, which defines double-precision floating point operations. The floating-point numbers comply with IEEE 754-2008 standardized by IEEE.

It is basically the same as single-precision floating-point operations (RV64F). The rounding modes are not properly implemented this time as well. (I’ll do it someday.)

January 5, 2020 (533ea69: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented RV64A, which defines the atomic instructions.

RV64A are instructions to maintain memory consistency across multiple hardware threads. In x86, an atomic instruction called compare-and-swap (CAS) is famously defined. It compares the contents of a memory location with a given value and, only if they are the same, modifies the contents of that memory location to a new given value. In other words, we can guarantee that the content of a particular memory location have not been changed. However, it just makes sure that the value has not changed, the thread that makes the compare-and-swap instruction may misidentify that “there was no change” because if another thread changes the original value A to a different value B, and then rewrites it to the original value A again, the value appears to remain A. This problem is called the ABA problem.

RISC-V adopted load-reserved (LR) and store-conditional (SC) instructions instead of compare-and-swap to avoid ABA problems. load-reserved reads a value from a specified address and stores the value in a register. In the store-conditional instruction, if there is any change in the reserved address, writing to the address will fail. Unlike compare-and-swap, which checks the value of an address, load-reserved/store-conditional avoids ABA problems because it monitors the address itself.

There are other atomic instructions such as amoadd which is adding atomically, etc. However, the emulator doesn’t operate them atomically since it only has one thread yet.

February 14, 2020 (a751a6b: src/cpu.rs)

RISC-V CPU has up to 4096 control and status registers (CSRs) that store CPU status. I implemented RV64Zicsr, which reads and writes the status registers.

February 18, 2020 (ba64dfa: src/exception.rs)

I implemented a part of the exception handling.

RISC-V defines the terms exception, interrupt, and trap as follows. These terms may be used differently depending on architectures and textbooks, but in this article we follow the definition of RISC-V.

- Exception: An unusual condition occurring at run time associated with an instruction in the current RISC-V hart.

- Interrupt: An external asynchronous event that may cause a RISC-V hart to experience an unexpected transfer of control.

- Trap: The transfer of control to a trap handler caused by either an exception or an interrupt.

There are currently 14 types of exceptions and a value indicating the type of exception is stored in the mcause control and status register when an exception occurs.

February 22, 2020 (6b6f7f9: src/cpu.rs)

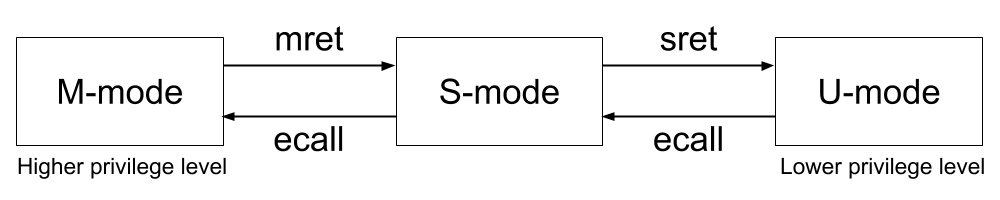

I implemented mret and sret instructions to transition privilege levels.

There are currently 3 types of privilege levels in RISC-V: machine mode (M-mode), user mode (U-mode), and supervisor mode (S-mode). All platforms must support the most primitive level, machine mode, and emulators up to this point had been running on machine mode.

A hardware that implements only machine mode is simple because it doesn’t have virtual address system and the CPU just executes the program instructions in order. It is useful when you don’t need complex functions in the field of embedded systems and you want to make the hardware smaller. On the other hand, if you want to run a complex system such as an OS, you need to implement all 3 types of modes.

The mret instruction is an instruction to move from the machine mode to other privilege levels. The next privilege level is determined by the value of the mpp field in mstatus. 0 means user mode, 1 means supervisor mode, and 3 means machine mode. The sret instruction is similarly an instruction to move from supervisor mode to other privilege levels.

March 4, 2020 (859d9fa: src/exception.rs)

I implemented ecall, which transitions privilege levels by raising an exception.

The ecall instruction raises an exception of environment-call-from-M-mode if the current privilege level is machine mode, environment-call-from-S-mode if supervisor mode, and environment-call-from-U-mode if user mode. Then it moves to a more privileged mode. It basically move to machine mode when an ecall is called, but the privilege level can be supervisor mode depending on the values in the medeleg and mideleg control and status registers.

ecall and mret/sret are a complementary relationship. A simplified overview of the privilege level transition is here:

March 9, 2020 (7cc38ab: src/devices/uart.rs)

I implemented UART (A universal asynchronous receiver-transmitter), which is a peripheral device for serial communication between the CPU and the outside the CPU.

RISC-V communicates with peripheral devices by memory-mapped I/O. Memory-mapped I/O is a method of exchanging data by reading and writing specific addresses where registers of peripheral devices exist, and can be handled by CPU in the same way as memory access. The location of a specific address is not listed in the RISC-V specifications and is (probably) determined by the designer of a motherboard. I adopted QEMU’s virt machine in this time.

If we look at the implementation of QEMU, we can see that UART is mapped from the position of 0x10000000 with the size of 0x100. In addition, if we look at the implementation of UART in xv6, it says “16550a UART” is adopted and the specification of this UART can be accessed from the web.

There are 5 types of registers in the specification but I just implemented the features used in xv6.

March 13, 2020 (ea77341: src/cpu.rs)

I implemented address translation by virtual memory system. A physical address is translated by the translate function before accessing the memory.

Until now, when the CPU specified an address, it would communicate with the memory and memory-mapped peripherals without modifying the address. This is called a physical address. When the virtual memory system is enabled, the address handled by the CPU is called a virtual address, and it is necessary to convert the address into a physical address. The virtual memory system is enabled by the value of the mode field in the stap control and status register. In hardware, MMU (memory management unit) is often in charge of address translation, but in this emulator it is implemented in CPU.

RISC-V defines 3 types of address translation methods: Sv32, Sv39, and Sv48. I implemented only Sv39 this time, which has a virtual memory address width of 39 bits so it can use up to 512GiB (=2**39) memory.

The address translation is done by the hardware page table walk. In Sv39, there are 3 levels of page tables which can be converted to physical addresses by tracing the elements of these tables.

March 16, 2020 (d690e52: src/devices/plic.rs)

I implemented PLIC (a platform-level interrupt controller) to control interrupts from peripheral devices.

PLIC is one of the memory mapped devices as well as UART, and if we look at the implementation of QEMU, we can see that PLIC is mapped from the position of 0xc000000 with the size of 0x4000000.

The main function of PLIC is to tell which peripheral interrupted which hardware thread. Xv6’s implementation of interrupts shows that the function plic_claim gets a value from PLIC that identifies which peripheral interrupted. Xv6’s implementation of PLIC shows that the function plic_claim just reads a memory-mapped value from PLIC_SCLAIM. Therefore, it should write a value that identifies the peripheral devices at this address when an interrupt occurs although it’s not implemented yet at this point.

March 18, 2020 (1e7964f: src/interrupt.rs)

I implemented interrupts.

Until now, UART and PLIC peripherals have only been able to read and write values that exist at memory-mapped addresses, but have not yet been able to make interrupts occur.

When an interrupt occurs, the value to identify the peripheral is written to the sclaim register in PLIC in src/interrupt.rs. This allows the interrupt handler in an OS to read this value and identify which peripheral device generated the interrupt.

March 18, 2020 (e535d27: src/devices/clint.rs)

I implemented CLINT (a core-local interruptor) for timer interrupts.

CLINT is one of the memory mapped devices as well as UART and PLIC, and the implementation of QEMU shows that CLINT is mapped from the position of 0x2000000 with the size of 0x10000.

If we look at the xv6 implementation that initializes a timer, we can see that the sum of the interval time (1000000) and MTIME is written to the CLINT_MTIMECMP position. A timer interrupt occurs when the value of the MTIME register, which counts the number of cycles executed by the CPU, becomes larger than MTIMECMP.

March 20, 2020 (c225992: src/devices/virtio.rs)

I implemented the part of reading and writing a disk via virtio which is a disk and network interface.

Virtio is one of the memory mapped devices as well as UART, PLIC and CLINT. If we look at the QEMU implementation, we can see that virtio is mapped from the position of 0x10001000 with the size of 0x1000.

I didn’t read virtio’s specification, but I implemented the emulator to support virtio_disk_rw which is a reading/writing function in the implementation of virtio’s driver on xv6. I also used takahirox/riscv-rust as a reference when implementing virtio.

Xv6 works now. The functions implemented so far are as follows. However, I haven’t been able to implement correctly rounding modes in floating-point numbers and atomicity in atomic instructions yet, but since xv6 is running, I don’t think the CPU instructions needed as much as I do.

- RV64G ISAs

- Privilege levels

- Control and status registers

- Virtual memory system (Sv39)

- UART

- CLINT

- PLIC

- Virtio

As a next step, I’m trying to support Linux on my emulator.

Thank you for reading this article. Comments and questions are always welcome to @d0iasm.